The Little Free Library, Part 2: Trash >>> Treasure

- fiction4

- Nov 13, 2025

- 4 min read

If you live in the U.S. or are familiar with American culture, you know that we became a super materialistic society in the mid-20th century. For this we can thank the post-WWII trends of rising income (for some), industrial expansion, and increasingly sophisticated marketing. We’re obsessed with things we want, with upgrading things we have, and – inevitably – with offloading stuff we don’t care about anymore. Way too many of our castoffs end up in landfill. But those of us interested in charity and conservation might seek to distribute our post-consumer items to people who want or need them.

Sharing Our Abundance

Conservation is a relatively new idea in human history (and the topic for a different discussion). Instead, let’s look at charity, a fundamental building block of civilization. Charity isn’t transaction; it’s inclusion. It’s a gesture that says, “You need something that I have, and I don’t want you to suffer because of that need.” Charity can be amplified when a community gives from a pool of common resources. In the modern sharing economy (because that’s now a thing), we have organizations and movements that make giving transactional, but it’s a soft transaction, more of an “isn’t this fun” exercise than a “this for that” exchange. Look at the coolness factor of the BuyNothing Project, the Freecycle Network, and Upcycle That for examples of how we share material abundance in the 21st century.

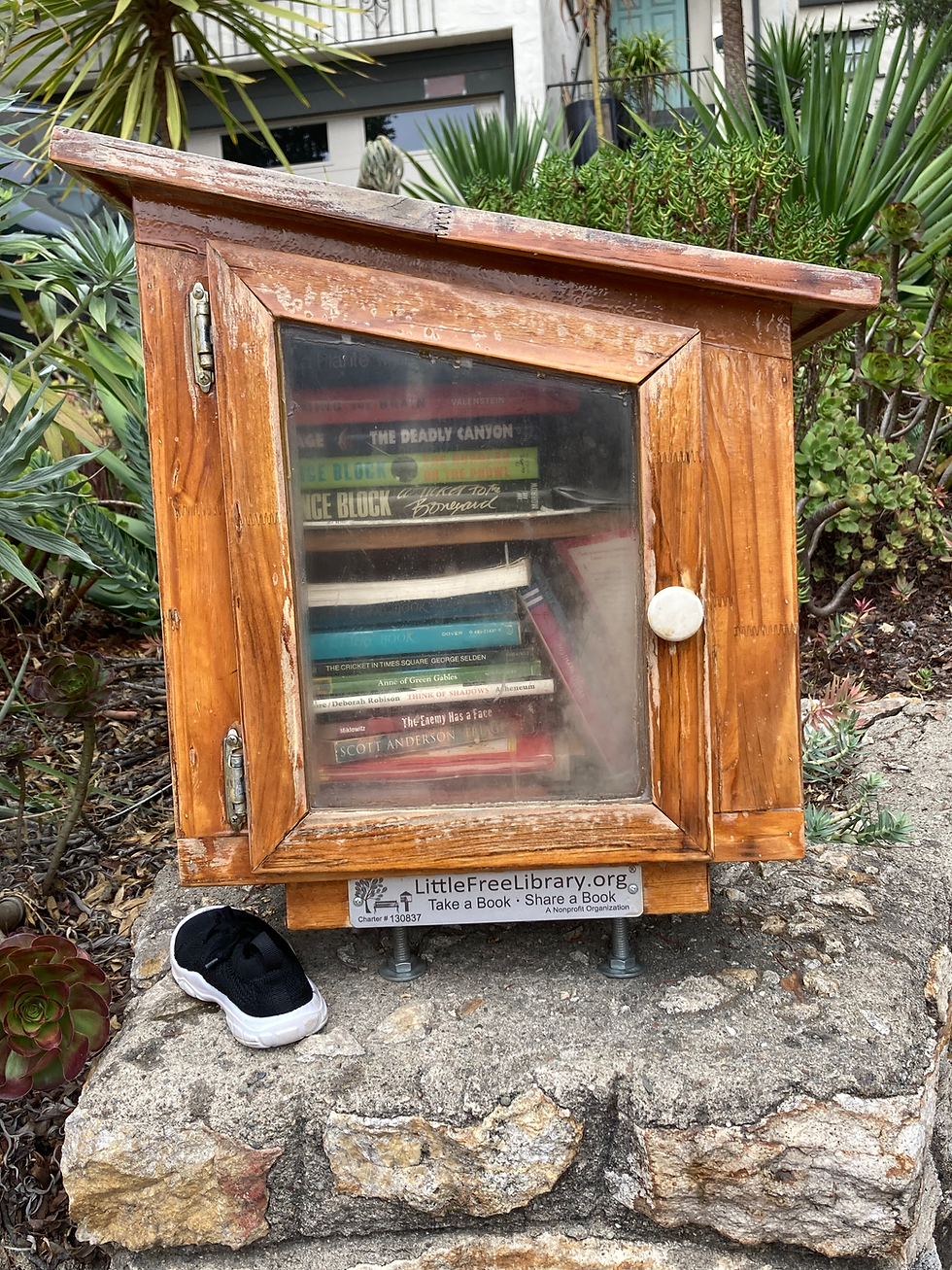

And to this list, we must also add the Little Free Library.

Throwaway Relics of Dying Technologies

A book is a simple form of technology, a means of containing and conveying written language. If you prefer to think of it as a product rather than a technology unto itself, we can certainly agree that we have books thanks to printing and distribution technologies. And where I live (and maybe where you live, too), there’s a glut of that material product. It’s been that way for a long time. This is a college town where until recently you couldn’t swing a cat without hitting a bookstore. Sure, you see folks everywhere with their eReaders, tablets, and phones, but many people still prefer books. Well, I can’t say that for sure. Maybe they used to prefer books and still have a houseful of them after amassing all their favorite titles on a Kindle. Or maybe they have years’ worth of assigned textbooks piling up on the shelf. Or maybe they see books as valuable even if not always useful.

What I can say for sure is that in places where people have switched their reading habits from page to screen, the product of printing and distribution technologies is flooding the curbside free boxes and the far-more-elegant Little Free Libraries. And you’d have to swing that proverbial cat in a wider arc because many bookstores are going away. The publishing industry has changed (a whole other topic), but while old-school readers rejoice at the glut of castoff books filling their nearest Little Free Library, this emerging system of free redistribution hasn’t done the bookstores any favors. I love bookstores. I’m sad to see them go away. But that battle is low on my list of things to fight for. There are only so many hours in a day.

Different Technology, More Relics

During the summer after COVID, as the world was cautiously unclenching, some unknown benefactor chose to liquidate their personal library of music CDs. Rather than selling everything to one of our beloved music stores, they went the public charity route and spent almost two months distributing their discs across the many Little Free Libraries at my end of town. I know this wealth originated from a single source because a lot of the jewel cases carried a distinctive smell of soap and cedar.

This unknown benefactor shared so many of my tastes – obscure progressive, mysterious classical (favoring medieval and baroque), edgy experimental, dreamy ambient, jazz you’ll never hear on the radio, and some of this stuff in box sets, no less! When I finally grasped what was happening, I started folding a cloth shopping bag in my pocket whenever I went out. Because there are only so many CDs by Focus, Claudio Monteverdi, Soul Coughing, John Zorn, Soft Machine, Hans Rott, and ECM-label artists that a person can carry in his bare hands!

All good things end, of course. Eventually that miracle of randomized anonymous giving tapered off. To this day, I still can’t see certain Little Free Libraries without thinking, “Ah! This is where I found that Peter Hammill box set during that one happy dog walk.”

Giving and Receiving

Music isn’t the only resource to appear in a free community distribution system that was designed for books. Looking through the glass doors of those colorful little structures, I sometimes see items of clothing, boxes of nonperishable food, and small potted plants. There are more traditional and obvious places to bring unwanted clothes (such as the Salvation Army) and extra food (many churches and community centers host food banks). And around here, you’ll see flats of succulent cuttings and little cacti sitting on many a curb with a “free” sign. However, at least in my town, the idea of random giving has gained a foothold under the roof of a recognizable little box. The Little Free Library is a kind of charitable brand, a redistribution system that everyone recognizes.

Even when you’re not in need of anything or in the mood to browse, it’s heartwarming to walk past a Little Free Library and know that someone made the effort to build a small shrine to abundance, to invite free taking and giving for anyone who walks by.

Comments